Featured Artist: Robin Birdd

Stepping into Robin Birdd’s studio reveals a collection of oddities ranging from the absurd to the unsettling. One corner houses a pile of breasts in a variety of sizes; from large sacks reminiscent of bean-bags to smaller, hand-sized pieces that tumble onto a nearby table. Birdd takes a seat at a desk, swiveling her chair to face me. Behind her a collection of milk crates store a variety of art supplies and notebooks, bowls containing paper cutouts rest on the tabletop beside a small sewing machine. Above the cluttered workstation are a number of shelves, which display drawings, masks, photographs and numerous vessels.

Birdd explains the breasts are part of a larger, collaborative installation planned for 2016. For this upcoming presentation, Birdd is creating an “adult playground” composed of taboo body parts, such as breasts and phalluses. Gesturing to the boob pile, Birdd tells me she plans on completing enough breasts to line a tunnel. Visitors will be allowed to crawl through the tunnel, as well as climb into a “sandbox” filled with grass and soft phallic sculptures. Birdd’s Danger Room pieces confront visitors with objects considered taboo in Western culture, and encourage adults to tap into their inner-child to play with these objects.

Throughout her work, Birdd explores childhood development and identity. She discusses the vital role family plays in the construct of one’s adult identity. “You’re a product of your family,” Birdd explains while offering me a cup of tea, “what you know is basically what they knew.” The concept of loosing one’s childhood innocence as one matures is present in nearly all of Birdd’s pieces and is the focus of the oil paintings currently displayed at The Midway.

Distorted depictions of families eating, embracing, and organizing themselves for a photo, are a sampling of Birdd’s Babies Making Babies series. The stark paintings capture everyday family activities, made abnormal by the occasional mutation.

Two women sit side by side at what could be a restaurant. One of them is eating noodles, holding chopsticks mid-air while nonchalantly staring at the viewer with a set of four eyes. Another painting depicts what appears to be a family birthday dinner. The skewed angle of the piece reads as a candid photograph with heads cropped off. At the far end of the table an elderly woman holds and feeds a small child. The child has two faces protruding from his heavily creased neck; he grimaces as he glances to something on his right.

Birdd shows me the photographs that inspired these paintings. The collection at the Midway is pulled from her boyfriend’s family photos. She tells me that the mutations symbolize the complex manifestation of one’s self-identity, understanding, and worldview as molded by the family one interacts with and the experiences and beliefs those family members expose one to. She also touches upon the lasting affects of trauma.

While trying to help me understand the context of her pieces, Birdd laughs as she recalls a moment from her childhood that may have had an affect on her present. “In my parents bathroom, underneath the sink, there was this Halloween mask and a giant boob mug that you were supposed to drink out of; along with some other storage. So, whenever my mom would be like, ‘Can you get the extra toothpaste underneath the sink,’ I would be terrified. Mainly because of the Halloween mask but also because of the boob,” she says chuckling.

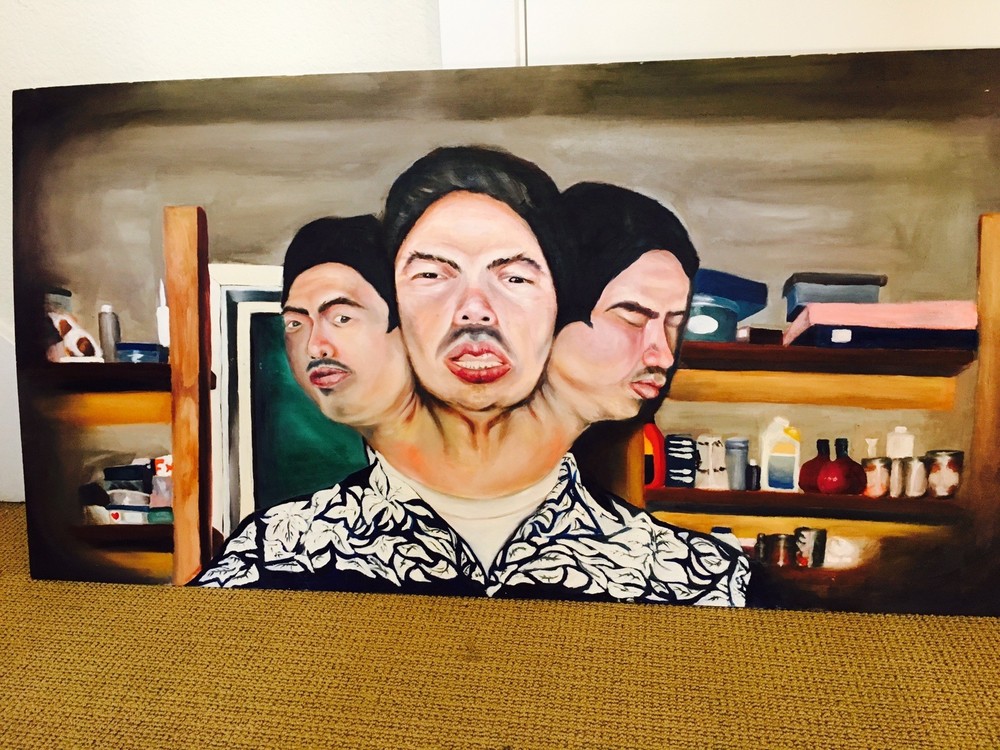

She goes on to tell me about her father who she describes as obsessed with Lil’ Kim and boastful of his promiscuity. Pointing to an unfinished painting leaning against the wall, Birdd reveals it’s a portrait of her father. She’s painted with three faces: the middle face defiantly looks directly out of the canvas, to it’s the right another face appears to cautiously glance toward the center face, to the center face’s left yet another face emerges with eyes closed and pouted lips. He stands wearing a navy blue and white floral print Hawaiian shirt.

Birdd describes her relationship with her father as good but perhaps weird to outsiders. Because her dad enjoys bragging about his sexual conquests, a running joke has been established in Birdd’s family to poke fun at his pride. Birdd acknowledges that humor may be used as a coping mechanism since it isn’t a topic kept hushed around her mother; but she believes it more strongly points to Filipino culture and the elements of machismo firmly engrained in her parents’ upbringing.

When I question Birdd on her mother’s opinion of her father’s behavior she responds that her mother is fine with it, that she accepts it. Birdd reasons that her mother’s mentality is partially influenced by catholic culture—the wife’s responsibility of keeping the family together—and her Filipino upbringing. She goes on to say that, in her household, one is expected to love family no matter what.

The Babies Making Babies series is Birdd’s master project, which she plans on expanding throughout her lifetime. Be sure to check out her work at The Midway’s intern-curated show, Contexture, open until December 14, 2015.

Written by: Vanessa Wilson

Photos taken by: Jacob Abern